Monday, June 21, 2010

The amazing shoulder - part 2: glenohumeral joint & muscles (yes rotator cuff too)

Follow @mcphoo

Tweet

In part one of this quick tour of the amazing shoulder we looked particularly at the shoulder girdle and the muscles that act pretty much directly on the scapula. The main take away was that significant muscles like the traps, rhomboids, pec minor, serratus anterior and levator scapula all work pretty much *just* to move the scapula and so reposition the shoulder joint socket to extend range of motion for the arm moving in the shoulder.

In this piece, we'll overview those pixie rotator cuff muscles and look at why they can be such a pain - in the shoulder - and how understanding the movements these muscles support may help reduce injury risk.

We'll also take a quick look at the big muscles like the lats that opperate on the main shoulder joint, the glenohumral joint. From here we'll speculate about shoulder injuries and habits to avoid them.

The shoulder tour part II: The Glenohumeral Action

Rotator Cuff What is it with the rotator cuff? we hear about so many injuries to the shoulder, and we likewise hear so much about the need to "prehab" these muscles to defeat injury. And i'm not a bystander here: i've likewise run my shoulder into the wall and shook my head to say "what is this pain? what is this thing? what needs to change? what the heck is wrong here?" I've had folks say "ah, that's the supraspinatus most like" -Um, could you unpack that a bit? No? ok. So here's a go at trying to get a little better understanding of a bit of what's happening with the rotator cuff.

First, the GlenoHumeral Joint. In moving to the rotator cuff, we're moving away from a focus on the shoulder girdle and the movement of the scapula to the main reason for the scapula: the gleno-humeral connection - or connecting the extremity that is the arm to the trunk of the body - the upper body in particular.

Where that connection takes place is with the humeral head of the humerous being knit into the glenoid cavity (or fossa) of the scapula. Note again the side view of the scapula - the glenoid fossa is rather shallow, but there's a liner/washer called the glenoid labrum that gets inset into that cavity before the humeral head makes contact. And then there's a capsule that goes around that unit, and ligaments around that. Those ligaments are kind of like a snugly-but-loosely laced sneakers - there's some give because of all the range of motion in the shoulder. This looseness - it's a bug; it's a feature.

Rotator Cuff Job 1 - holding ball in socket.

Just for context, there are four rotator cuff muscles: 1 on top, the SUPRAspinatus, 1 covering the front that goes against the underside of the scapula that is against the ribs the SUBscapularis, and two on the back of the scapula, the infraspinatus and and the teres minor

The top muscle, the supraspinatus (supra=above the spiney bit), attaches from the top of the scapula at the big scapula spine, runs along the top of that ridge, goes under the acromium process of the scapular spine, over the bursa on the top of the glenohumeral capsule and then attaches onto a big bump at the top of the humerus, the greater tubercle. That is a very popular attachment point - like the superior spine of the scapula but much smaller a peak. So when this muscle contracts, it's going to help pull the arm up to 90 degrees from one's side - called abduction. Note i say "help" - we'll come back to this assistance role. Mainly it's stabilizing the ball of the humerus in the glenoid socket.

The subscapularis which attaches along the entire scapula underside (the scapula fossa) the attaches around the front of the humerus at the lesser tubercle. If you imagine these fibers contracting, they're going to contribute to turning the humerus in (internal rotation), pulling the humerus across the body, pulling the arm back (into extension) and, of course 'stabilizing the humeral head in the glenoid fosa' - as the manual of structural kinesiology puts it.

puts it.

The infraspinatus is the complement to the subscapularis: subscapularis = under(side) of the scapula; infraspinatus means below the spiney bit. Names are nicely descriptive. Where the subscapularis covers the underside of the scapula, the infraspinatus covers the whole backside of the scapula below that big scapular spine. Where the supraspinatus attaches to the top of the greater tubercle, the infraspinatus attaches to the back of the greater tubercle. So again, if we imagine pulling / contracting that attachment, the kinds of things that can happen to the arm are - its turned out (externally rotated), it's also going to pull the arm back into extension. It also helps with what's known as horizontal abduction. Big role - stabilize the arm in the socket - we might add especially when it's being moved about.

The teres minor is like a support for the infraspinatus. Teres just means round and smooth (cylyndrical). and that's sort of what this muscle is. It hangs onto the lateral border of the scapula (the edge closer to the arm), and then plugs in under the greater tubercle of the humerus. So what's it going to do? Exactly the same as the infraspinatus: *stabilization,*external rotation, extension and horizontal abduction.

Note: horizontal abduction is different from abduction: abduction, the arm is being raised up at the side; horizontal abduction assumes that the arm is already up at ninety degrees and infront of the body, and so the arm is being pulled back (abduction - ab is latin for from, as in away from rather that ad, to, towards).

Summary of RCM Action That's it: 4 muscles with pretty functionally descriptive names.

They all have four things in common:

They're so WEAK, what's the point of being muscles?

In reading kinesiology texts, a word repeated all the time about the rotator cuff muscles is "weak" - they provide weak adduction, weak abduction, weak rotation - weak weak weak. no leverage. like a person trying to open a door when the handle is in the middle of the door.

If they're so weak what are they doing there? One of the best reframings of the roll of the RCMs is in the Anatomy of Movement . There Calais-Germain uses the term "active ligaments" to describe the function of these muscles. Considering that it's the tendon part of the muscles that usually comes to grief when we talk about overuse injuries or RC problems, gosh that makes sense. Ligaments are pretty fixed things - little stretch - that are used to support attachments around joints and often over joint capsules. In many ways, the RCM's mirror this role.

. There Calais-Germain uses the term "active ligaments" to describe the function of these muscles. Considering that it's the tendon part of the muscles that usually comes to grief when we talk about overuse injuries or RC problems, gosh that makes sense. Ligaments are pretty fixed things - little stretch - that are used to support attachments around joints and often over joint capsules. In many ways, the RCM's mirror this role.

Indeed, every movement that a muscle in the rotator cuff supports "weakly" there is a complementary big muscle to do, literally, the heavy lifting. So let's look at these big lifters next.

Extrinsic muscles of the glenohumeral joint: the heavy lifters. The big movers of the arm are the deltoids, mapping mainly to the action of the supraspinatus, the lats, mapping mainly to the infraspinatus and teres minor, and the pecs with the subscapularis. Mainly. There's also the corachoid brachialis, a small but potent flexor.

The deltoid is usually considered the main "shoulder" muscle. It's a goodly three part triangular mass that connects on both the first third of the scapula, around the front of the acromion process and into the under edge of the scap spine. And the next big deal is that it attaches to the humerous at its very own "deltoid tuberosity" of the humerus.

The deltoid is usually considered the main "shoulder" muscle. It's a goodly three part triangular mass that connects on both the first third of the scapula, around the front of the acromion process and into the under edge of the scap spine. And the next big deal is that it attaches to the humerous at its very own "deltoid tuberosity" of the humerus.

So what's it do? This will sound familiar: the front bits will elevate the arm (abduct) and going past that, flexion the arm, as well as turn the arm in. The mid part will also abduct or lift the arm up to the side - as in a "side lateral raise" move. And the back part will do that horizontal abduction thing while rotating the arm out. So front rotates in; back rotates out. Cool that one muscle has these opposing motions within it.

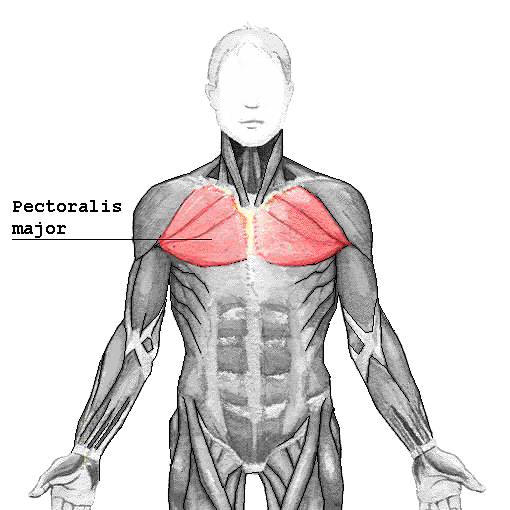

The pec major - the big chest muscle - likewise has mutlipte parts: upper or clavicular and lower or sternal.

The pec major - the big chest muscle - likewise has mutlipte parts: upper or clavicular and lower or sternal.

The muscle attaches around the clavicle at the top and then along the sternum (middle of the rib cage). It plugs into the frontish of the humerous at yet another tubercle, the "intertubercular groove."

The pec's upper fibers turns the arm in as well as pulling the arm across in horizontal adduction. We see horizontal adduction when we bear hug someone. The lower fibers also support horizontal adduction and internal rotation, but they also complement the lats' action of extension from flexion down to neutral (arm at side).

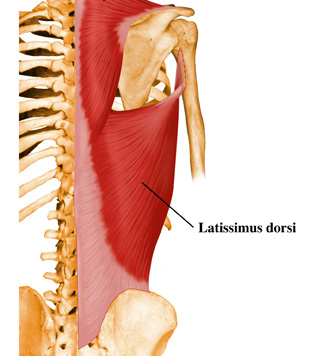

The lats - i've written about the action of the latisimus dorsi in relation to the pull up and the swing elsewhere. Suffice it to say here that it's a great big muscle that runs along the bottom half of the thoracic spine and into/onto the hip and attaches to the inside (medial lip) of the humerus.

The action here is to pull the arm back (horizontal abduction) also to extend the arm back down (extention) past where the pecs can get to, rotate the arm in, and bring it down/across the body.

Aside - you've likely noted that with the body, if there's a greater somewhere there's a lesser; if there's a minor there's a major.

The Little Lats: the Teres Major Tucked away on the back of teh scapula is one more muscle - the teres major. It is not a rotator cuff muscle; it attaches on the humerous not up at the head but just behind where the lats attahes at the medial lip of the intertubercular groove. It's main action difference from the lats is that, when the arm is out at the side (abducted) it helps pull the arm back down to the side.

It complements the lats, the pecs and works with the rhomboids.

RCM vs Extrinsic Muscles - Local vs Global or Hinges vs Handles.

So what's with the duplication of effort between the rotator cuff muscles (intrinsic g/h muscles) and these big muscles? If we use the model of active ligaments for the rotator cuff, i think we're away: the RCM's have the local job of just focusing on the socket: keeping the humeral head in that fosa and supporting that contact while the joint is moving. Snug snug snug. Hang on tight.

The big muscles are all about levers - all about really lifting the whole upper arm up, out, over, down, across and back with load. And to do big lifts we need both big fat rope and length.

Consider openning a door. The hinges hold the door in place and hold it up - they're close to the edge of the plank that moves around the door attached to the lintel. Great. They're not huge, but they're strong and do the hinge job nicely of keeping the door in place and letting it move when it's moved.

But what does this big moving action? The big handle on the door enables force to be used to open the door more easily. We know with heavy doors, some handles are also really big bars and can be grabbed with both hands. Why so far from the hinge and so big? If the handle were right close to the hinge, or even in the middle of the door - short lever - a heavy door is hard to open - maybe immovable. Indeed, putting a lot of force on a small handle close to a hinge may simply wreck the handle and still not open the door.

When the handle is close to the end opposite the hinge, then the width of the door becomes the length of the lever and a longer lever (in this case acting like a wheel barrow type lever) can make a big door easy or easier to move. Having a big handle means more force can be applied more easily, to the lever as well. Consider the teres major on the scapula complementing the pull on the humerus of the lat - kinda like a two handed pull.

Likewise, we can look at position: the pecs pull from the arm to the furthest possible point away - the middle of the front of the body. The lats also go to the arm from the middle of the back of the body. With the delts, which are well supported by the pecs and the lats - likewise these muscles run almost to the middle of the top of the scap and the clavicle and then into near the middle of the humerus, like a tetter totter.

So why all these injuries? A modest proposal.

SO if the rotator cuffs are just support muscles, and there are these big levers to move the arm when loaded, why are they getting hurt so much of the time? That's a good question. Let's assume we're not talking about accidents where someone flies into one's shoulder, rips it off, or one falls on the shoulder and dislocates it, ripping tendons. Or let's also assume there's not some genetic defect that causes tendons to rub against a deformation in bone. From here, it seems a biggie issue in athletes is "overuse" injuries of various kinds, resutling in various kinds of tendinopathies (discussed with respect to the shoulder, over here).

When do these kinds of injuries usually happen? For instance why do i get issues with my left shoulder not my right? After months of double pressing was i listening to my left shoulder or my right during sets? was i relecutant to stop when my left may have been flagging a little more than my right? did that cause me to hyperextend my shoulder a bit, and cause the supraspinatus to rub against the acromium and inflame and pull and get messed up?

In other words, can a lot of overuse injuries be put down to form failure of one kind or another? Shoulder overuse issues are really common in swimming apparently - is one side of teh stroke less perfect than the other causing the support muscles to do more work than the big muscles?

Practice to avoid Failure?

There are lots of folks who have lots of programs for strengthening the rotator cuff, rehabbing it and all that. Maybe that's great and appropriate. Me, i'm wondering however if focusing on the site is missing the source of an issue. How often is an overuse injury for instance the fault of the little muscle that pays the price rather than limitations in the effectiveness of the big muscles?

How might one know? My bias is a movement assessment.

Consider if the problem in the shoulder is from lack of good mobility in the thoracic spine. Or if the issue has to do with poor firing of the lat to support the shoulder. Will rotator cuff-focused rehab hit these issues? In other words, my bias is to consider at least first what the larger movement issues may be and work from there.

Consider if the problem in the shoulder is from lack of good mobility in the thoracic spine. Or if the issue has to do with poor firing of the lat to support the shoulder. Will rotator cuff-focused rehab hit these issues? In other words, my bias is to consider at least first what the larger movement issues may be and work from there.

How might one address the issue? Suppose one has done their movement assessment and has a bunch of specific movement oriented work. Then joint mobility work as part of normal practice, and exercises that support one's practice (like the turkish get up and the windmill for the shoulder) are going to assist in good holistic movement.

Likewise, everyone needs a coach. It really pays to have an experienced coach look at our form and critique it and tune it. Some of us have never had an expert look at our movement. Hopefully the complexity of the above muscular interaction will provide good reason to make sure the movements we are performing are optimally supporting the way we move best to perform an exercise - and to be ready to quit when that form fails.

Summary

Scapula Moves for Greater ROM. In the first part of this series, we saw that the scapula moves up and down, back and forth and rotates up and down too for depression, elevation protraction retraction upward and downward rotation - all to extend the possible range of motion of the shoulder

RCMs In this part of the series we've seen how the arm that the scapula is moving about to extend its reach is both held to the body at the joint via the rotator cuff muscles - and more particularly how the big movers like the lats and the pecs especially and the delts in concert with these actually LIFT the arm up down around and back from these various scapular positions.

Glenohumeral Joint We've considered the role of the rotator cuff as local stabilizers or "active ligaments" to keep the arm in the socket for when the global levers of muscles are moving the humerus through its range of motion especially with load. That the rotator cuff muscles are like door hinges to hold the door in place so it can move, and that the big muscles are like the action on the well positioned lever to open the door.

Based on this model, we've considered that when injuries to the little support muscles occur it may be not always be becuase of particular weakness on their part but because of more systemic failure on the part of the grosser movement. As such, tuning our movement is a good idea, and we can do this by working on the range of motion of our joints, our movement quality with practice of rich multiplanar movements like the turkish get up and windmill, and that we can get a pair of pracitced eyes on our form at least from time to time to ensure we're moveing as well as we think we are.

Coda

This two part series is by no means exhaustive in terms of the shoulder girdle or joint - i haven't even touched on the role of the clavicle or the role of elbow flexors and extensors that connect into the shoulder. Nor have we talked about the nerves running through the shoulder and how neck mobility can consequently help with shoulder movement.

Really this two parter has just been meant to share some appreciation of the three core components of shoulder movement: that the scapula moves to support range of motion; that the rotator cuff holds the arm moving with that scapula and that the big arm movers lift/pull that arm as its stabilized in that joint. That story is told in the amazingly odd shape of the scapula.

I hope these pieces may inspire folks to explore a little deeper or at least help make a bit more sense of what's happening in the shoulder and from here help make a bit more sense of our own movement practice.

Any mistakes in here - including soggy analogies - are mine.

best

mc

Related

In this piece, we'll overview those pixie rotator cuff muscles and look at why they can be such a pain - in the shoulder - and how understanding the movements these muscles support may help reduce injury risk.

We'll also take a quick look at the big muscles like the lats that opperate on the main shoulder joint, the glenohumral joint. From here we'll speculate about shoulder injuries and habits to avoid them.

The shoulder tour part II: The Glenohumeral Action

Rotator Cuff What is it with the rotator cuff? we hear about so many injuries to the shoulder, and we likewise hear so much about the need to "prehab" these muscles to defeat injury. And i'm not a bystander here: i've likewise run my shoulder into the wall and shook my head to say "what is this pain? what is this thing? what needs to change? what the heck is wrong here?" I've had folks say "ah, that's the supraspinatus most like" -Um, could you unpack that a bit? No? ok. So here's a go at trying to get a little better understanding of a bit of what's happening with the rotator cuff.

First, the GlenoHumeral Joint. In moving to the rotator cuff, we're moving away from a focus on the shoulder girdle and the movement of the scapula to the main reason for the scapula: the gleno-humeral connection - or connecting the extremity that is the arm to the trunk of the body - the upper body in particular.

Where that connection takes place is with the humeral head of the humerous being knit into the glenoid cavity (or fossa) of the scapula. Note again the side view of the scapula - the glenoid fossa is rather shallow, but there's a liner/washer called the glenoid labrum that gets inset into that cavity before the humeral head makes contact. And then there's a capsule that goes around that unit, and ligaments around that. Those ligaments are kind of like a snugly-but-loosely laced sneakers - there's some give because of all the range of motion in the shoulder. This looseness - it's a bug; it's a feature.

Rotator Cuff Job 1 - holding ball in socket.

Just for context, there are four rotator cuff muscles: 1 on top, the SUPRAspinatus, 1 covering the front that goes against the underside of the scapula that is against the ribs the SUBscapularis, and two on the back of the scapula, the infraspinatus and and the teres minor

The top muscle, the supraspinatus (supra=above the spiney bit), attaches from the top of the scapula at the big scapula spine, runs along the top of that ridge, goes under the acromium process of the scapular spine, over the bursa on the top of the glenohumeral capsule and then attaches onto a big bump at the top of the humerus, the greater tubercle. That is a very popular attachment point - like the superior spine of the scapula but much smaller a peak. So when this muscle contracts, it's going to help pull the arm up to 90 degrees from one's side - called abduction. Note i say "help" - we'll come back to this assistance role. Mainly it's stabilizing the ball of the humerus in the glenoid socket.

The subscapularis which attaches along the entire scapula underside (the scapula fossa) the attaches around the front of the humerus at the lesser tubercle. If you imagine these fibers contracting, they're going to contribute to turning the humerus in (internal rotation), pulling the humerus across the body, pulling the arm back (into extension) and, of course 'stabilizing the humeral head in the glenoid fosa' - as the manual of structural kinesiology

The infraspinatus is the complement to the subscapularis: subscapularis = under(side) of the scapula; infraspinatus means below the spiney bit. Names are nicely descriptive. Where the subscapularis covers the underside of the scapula, the infraspinatus covers the whole backside of the scapula below that big scapular spine. Where the supraspinatus attaches to the top of the greater tubercle, the infraspinatus attaches to the back of the greater tubercle. So again, if we imagine pulling / contracting that attachment, the kinds of things that can happen to the arm are - its turned out (externally rotated), it's also going to pull the arm back into extension. It also helps with what's known as horizontal abduction. Big role - stabilize the arm in the socket - we might add especially when it's being moved about.

The teres minor is like a support for the infraspinatus. Teres just means round and smooth (cylyndrical). and that's sort of what this muscle is. It hangs onto the lateral border of the scapula (the edge closer to the arm), and then plugs in under the greater tubercle of the humerus. So what's it going to do? Exactly the same as the infraspinatus: *stabilization,*external rotation, extension and horizontal abduction.

Note: horizontal abduction is different from abduction: abduction, the arm is being raised up at the side; horizontal abduction assumes that the arm is already up at ninety degrees and infront of the body, and so the arm is being pulled back (abduction - ab is latin for from, as in away from rather that ad, to, towards).

Summary of RCM Action That's it: 4 muscles with pretty functionally descriptive names.

They all have four things in common:

- they all attach to the scapula

- they each attach near the humeral head

- they all primarily stabilize the the arm in its socket.

- they all rotate the arm in the socket either up, in or out (hence the name, rotator)

They're so WEAK, what's the point of being muscles?

In reading kinesiology texts, a word repeated all the time about the rotator cuff muscles is "weak" - they provide weak adduction, weak abduction, weak rotation - weak weak weak. no leverage. like a person trying to open a door when the handle is in the middle of the door.

If they're so weak what are they doing there? One of the best reframings of the roll of the RCMs is in the Anatomy of Movement

Indeed, every movement that a muscle in the rotator cuff supports "weakly" there is a complementary big muscle to do, literally, the heavy lifting. So let's look at these big lifters next.

Extrinsic muscles of the glenohumeral joint: the heavy lifters. The big movers of the arm are the deltoids, mapping mainly to the action of the supraspinatus, the lats, mapping mainly to the infraspinatus and teres minor, and the pecs with the subscapularis. Mainly. There's also the corachoid brachialis, a small but potent flexor.

The deltoid is usually considered the main "shoulder" muscle. It's a goodly three part triangular mass that connects on both the first third of the scapula, around the front of the acromion process and into the under edge of the scap spine. And the next big deal is that it attaches to the humerous at its very own "deltoid tuberosity" of the humerus.

The deltoid is usually considered the main "shoulder" muscle. It's a goodly three part triangular mass that connects on both the first third of the scapula, around the front of the acromion process and into the under edge of the scap spine. And the next big deal is that it attaches to the humerous at its very own "deltoid tuberosity" of the humerus.So what's it do? This will sound familiar: the front bits will elevate the arm (abduct) and going past that, flexion the arm, as well as turn the arm in. The mid part will also abduct or lift the arm up to the side - as in a "side lateral raise" move. And the back part will do that horizontal abduction thing while rotating the arm out. So front rotates in; back rotates out. Cool that one muscle has these opposing motions within it.

The pec major - the big chest muscle - likewise has mutlipte parts: upper or clavicular and lower or sternal.

The pec major - the big chest muscle - likewise has mutlipte parts: upper or clavicular and lower or sternal.The muscle attaches around the clavicle at the top and then along the sternum (middle of the rib cage). It plugs into the frontish of the humerous at yet another tubercle, the "intertubercular groove."

The pec's upper fibers turns the arm in as well as pulling the arm across in horizontal adduction. We see horizontal adduction when we bear hug someone. The lower fibers also support horizontal adduction and internal rotation, but they also complement the lats' action of extension from flexion down to neutral (arm at side).

The lats - i've written about the action of the latisimus dorsi in relation to the pull up and the swing elsewhere. Suffice it to say here that it's a great big muscle that runs along the bottom half of the thoracic spine and into/onto the hip and attaches to the inside (medial lip) of the humerus.

The action here is to pull the arm back (horizontal abduction) also to extend the arm back down (extention) past where the pecs can get to, rotate the arm in, and bring it down/across the body.

Aside - you've likely noted that with the body, if there's a greater somewhere there's a lesser; if there's a minor there's a major.

The Little Lats: the Teres Major Tucked away on the back of teh scapula is one more muscle - the teres major. It is not a rotator cuff muscle; it attaches on the humerous not up at the head but just behind where the lats attahes at the medial lip of the intertubercular groove. It's main action difference from the lats is that, when the arm is out at the side (abducted) it helps pull the arm back down to the side.

It complements the lats, the pecs and works with the rhomboids.

RCM vs Extrinsic Muscles - Local vs Global or Hinges vs Handles.

So what's with the duplication of effort between the rotator cuff muscles (intrinsic g/h muscles) and these big muscles? If we use the model of active ligaments for the rotator cuff, i think we're away: the RCM's have the local job of just focusing on the socket: keeping the humeral head in that fosa and supporting that contact while the joint is moving. Snug snug snug. Hang on tight.

The big muscles are all about levers - all about really lifting the whole upper arm up, out, over, down, across and back with load. And to do big lifts we need both big fat rope and length.

Consider openning a door. The hinges hold the door in place and hold it up - they're close to the edge of the plank that moves around the door attached to the lintel. Great. They're not huge, but they're strong and do the hinge job nicely of keeping the door in place and letting it move when it's moved.

But what does this big moving action? The big handle on the door enables force to be used to open the door more easily. We know with heavy doors, some handles are also really big bars and can be grabbed with both hands. Why so far from the hinge and so big? If the handle were right close to the hinge, or even in the middle of the door - short lever - a heavy door is hard to open - maybe immovable. Indeed, putting a lot of force on a small handle close to a hinge may simply wreck the handle and still not open the door.

When the handle is close to the end opposite the hinge, then the width of the door becomes the length of the lever and a longer lever (in this case acting like a wheel barrow type lever) can make a big door easy or easier to move. Having a big handle means more force can be applied more easily, to the lever as well. Consider the teres major on the scapula complementing the pull on the humerus of the lat - kinda like a two handed pull.

Likewise, we can look at position: the pecs pull from the arm to the furthest possible point away - the middle of the front of the body. The lats also go to the arm from the middle of the back of the body. With the delts, which are well supported by the pecs and the lats - likewise these muscles run almost to the middle of the top of the scap and the clavicle and then into near the middle of the humerus, like a tetter totter.

So why all these injuries? A modest proposal.

SO if the rotator cuffs are just support muscles, and there are these big levers to move the arm when loaded, why are they getting hurt so much of the time? That's a good question. Let's assume we're not talking about accidents where someone flies into one's shoulder, rips it off, or one falls on the shoulder and dislocates it, ripping tendons. Or let's also assume there's not some genetic defect that causes tendons to rub against a deformation in bone. From here, it seems a biggie issue in athletes is "overuse" injuries of various kinds, resutling in various kinds of tendinopathies (discussed with respect to the shoulder, over here).

When do these kinds of injuries usually happen? For instance why do i get issues with my left shoulder not my right? After months of double pressing was i listening to my left shoulder or my right during sets? was i relecutant to stop when my left may have been flagging a little more than my right? did that cause me to hyperextend my shoulder a bit, and cause the supraspinatus to rub against the acromium and inflame and pull and get messed up?

In other words, can a lot of overuse injuries be put down to form failure of one kind or another? Shoulder overuse issues are really common in swimming apparently - is one side of teh stroke less perfect than the other causing the support muscles to do more work than the big muscles?

Practice to avoid Failure?

There are lots of folks who have lots of programs for strengthening the rotator cuff, rehabbing it and all that. Maybe that's great and appropriate. Me, i'm wondering however if focusing on the site is missing the source of an issue. How often is an overuse injury for instance the fault of the little muscle that pays the price rather than limitations in the effectiveness of the big muscles?

How might one know? My bias is a movement assessment.

Consider if the problem in the shoulder is from lack of good mobility in the thoracic spine. Or if the issue has to do with poor firing of the lat to support the shoulder. Will rotator cuff-focused rehab hit these issues? In other words, my bias is to consider at least first what the larger movement issues may be and work from there.

Consider if the problem in the shoulder is from lack of good mobility in the thoracic spine. Or if the issue has to do with poor firing of the lat to support the shoulder. Will rotator cuff-focused rehab hit these issues? In other words, my bias is to consider at least first what the larger movement issues may be and work from there. How might one address the issue? Suppose one has done their movement assessment and has a bunch of specific movement oriented work. Then joint mobility work as part of normal practice, and exercises that support one's practice (like the turkish get up and the windmill for the shoulder) are going to assist in good holistic movement.

Likewise, everyone needs a coach. It really pays to have an experienced coach look at our form and critique it and tune it. Some of us have never had an expert look at our movement. Hopefully the complexity of the above muscular interaction will provide good reason to make sure the movements we are performing are optimally supporting the way we move best to perform an exercise - and to be ready to quit when that form fails.

Summary

Scapula Moves for Greater ROM. In the first part of this series, we saw that the scapula moves up and down, back and forth and rotates up and down too for depression, elevation protraction retraction upward and downward rotation - all to extend the possible range of motion of the shoulder

RCMs In this part of the series we've seen how the arm that the scapula is moving about to extend its reach is both held to the body at the joint via the rotator cuff muscles - and more particularly how the big movers like the lats and the pecs especially and the delts in concert with these actually LIFT the arm up down around and back from these various scapular positions.

Glenohumeral Joint We've considered the role of the rotator cuff as local stabilizers or "active ligaments" to keep the arm in the socket for when the global levers of muscles are moving the humerus through its range of motion especially with load. That the rotator cuff muscles are like door hinges to hold the door in place so it can move, and that the big muscles are like the action on the well positioned lever to open the door.

Based on this model, we've considered that when injuries to the little support muscles occur it may be not always be becuase of particular weakness on their part but because of more systemic failure on the part of the grosser movement. As such, tuning our movement is a good idea, and we can do this by working on the range of motion of our joints, our movement quality with practice of rich multiplanar movements like the turkish get up and windmill, and that we can get a pair of pracitced eyes on our form at least from time to time to ensure we're moveing as well as we think we are.

Coda

This two part series is by no means exhaustive in terms of the shoulder girdle or joint - i haven't even touched on the role of the clavicle or the role of elbow flexors and extensors that connect into the shoulder. Nor have we talked about the nerves running through the shoulder and how neck mobility can consequently help with shoulder movement.

Really this two parter has just been meant to share some appreciation of the three core components of shoulder movement: that the scapula moves to support range of motion; that the rotator cuff holds the arm moving with that scapula and that the big arm movers lift/pull that arm as its stabilized in that joint. That story is told in the amazingly odd shape of the scapula.

I hope these pieces may inspire folks to explore a little deeper or at least help make a bit more sense of what's happening in the shoulder and from here help make a bit more sense of our own movement practice.

Any mistakes in here - including soggy analogies - are mine.

best

mc

Related

- part 1 of the amazing shoulder: the scapula and shoulder girdle

- why move or die?

- what's mobility pracice?

- training to avoid the sprain: iphase

- nice piece in am. fam. physician on shoulder instability

- nice ref on SLAP tears in the context of baseball players - great figures.

Labels:

glenohumeral,

shoulder

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

COACHING with dr. m.c.

COACHING with dr. m.c.

6 comments:

Great great great article MC. Really excellent. This is so important as so many trainers have NO idea of the anatomy or kinesiology of this SO important area.

Thank you.

thanks for taking the time to post mark, and for your kind words.

mc

Nicely stated mc. I sometimes forget why I became a trainer. HELP fix what is broken, so that the person can perform as they want. Almost everyone has a shoulder issue, it just stems from something else (usually!)

Thanks for the reminder.

Interesting that you should be writing about this mc. I've had an issue with my right shoulder for a number of weeks now.

I shall have to book a session with you to see if you can help me with it.

Colin

thank you Chad; colin so sorry to hear about your shoulder. reduce load; reduce range of motion to stay out of pain till getting it super sorted. best

mc

Will do - cheers mc

Post a Comment