In the previous two posts about the

Ottoman Pistol we looked at the main muscles that are at play in this version of that assisted version of the one legged squat: the

quads (pt 1) and the

hamstrings and butt (pt 2).

The Ankle. In this post we're looking at the last part of this series, and it's less about muscle work and more about movement. It's

what happens at the ankles. Why bother to look at movement rather than muscle? It's the last key bendy bit of the move, if you will, and because we usually focus on the muscle side, we can kinda forget that the ankle joint is a key lever (with the knee and the hip) that lets that squat happen. Indeed in full pistols, you'll often hear folks talk about their ankles either a) supposedly not having enough flexibility or b) they cave into the side or c) can't stay down.

Take a look at Franz Snideman's great video series on his revelations through the whole pistol for more.

So for today, it might be fun if not just interesting to take a look at what's going on around this wild joint.

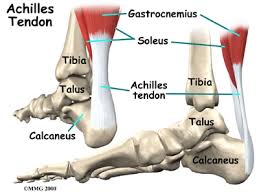

Gastrocnemius and Soleus (S&G) First off, we're likely pretty familiar with the big muscles that work the ankle. They are the gastrocnemius (gastrocs for short) and soleus. They're what let us do calf raises, go on point, help control the foot kicking a football. These muscles are usually really strong in just about anyone. Indeed, if they actually test weak, it's likely sign of some other issue that problems with these the S&G.

Two interesting things about the S&G (well i think so): they both connect into the one tendon in the body most of us know by its nick name: the achiles tendon (or tendo calcaneus, formally). It comes from the base of the muscles down the lower part of the lower leg and into the back of the back bone of the foot, that bone being the calcaneus. Contract those muscles, we pull up on that bone, we point our toes. That's the first interesting thing: the achiles tendon connection.

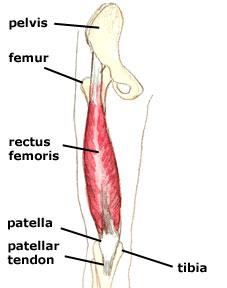

Different Origins. The second cool thing is that while they both connect to the same place at their insertions, the origin of each (the parts closest to the middle of the body) are very different - which kinda helps understand why we have both an S and a G rather than just one big muslce. The design also reflects how important this movement is (technically ankle plantar flexion, or bending towards the base of the foot).

|

different origins of the S (on the tibia) and G (on the femur)

one crosses the knee (G); the other doesn't. |

The Soleus tucks in underneath the gastrocs and it connects along the upper shaft of the big bone of the lower leg, the tibia. We'll come back to that in a moment. The keen thing here is that the muscle is dedicated to *just* flexing the ankle down, and it's a biggie. The gastrocs on the other hand, kinda like the reins on a horse, goes around to the frontish of the femur. In other words, it crosses at the knee joint and so not only has an effect on the ankle, but also pulls on the knee to help bend/flex it.

Bottom line, there's a lot of muscle to help flex the foot, and flex the foot down while helping bend the knee.

Super geeky aside: 2nd class lever. Plantar flexion of the foot when used to lift some or all of the body is one of the few examples in the body of what's know as a second class lever where the resistance (or load) is between the axis and the force. The usual example is a wheel barrow. The resistance is the load; the axis is at the wheel (ahead of the resistance) and the force is in the handles (behind the resistance).

If we look at the ankle - where to we see these three things? It's kinda clear that the pull or the force is at the achilles tendon on the calcaneus, right? So where's the axis or fulcrum? This only really comes into play when the foot is actually being used as a lever - as something to move something else (in physics the definition of work is the movement of an object). So, the ball of the foot (unless we're going on point perhaps) is the usual fulcrum of this lever (analogous to the wheelbarrow wheel). The resistance or load becomes effectively the stuff up through the tibia. The tibia, as we see is between the force and the axis/fulcrum. Jeeze that's cool.

Action in Pistol: More Eccentric Contraction. Just as we saw with the muscles of the knee and hip managing eccentric contraction to control lowering of the hip and of the knee (flexion), we're going to see the same eccentric contraction in the S&G for letting the lower leg roll forward at the ankle into dorsiflexion - the opposite of plantar flexion. Dorsiflexion has the angle between the top of the foot and the top of the shin decrease - which is exactly the motion that occurs as we squat down and the shin moves forward relative to the planted foot. The big soleus and gastrocs then pay themselves out under control to support the motion around the ankle. How cool is that?

|

the bumpy bits of the ankle

that we feel or see is really the

bumpy bits at the bottom of the TWO

bones of the shin: the tibia (big inside one)

and the fibula (leaner outside one) |

Meanwhile, at the front of the leg, the tibialis anterior, peroneus tertius and related smaller extensor muscles are going to help by contracting at the front of the shin to help that forward action of dorsiflexon take place.

The ankle joint: wild bones wild bones. One of the amazing things about this joint we tend to take for granted is actually how sophisticated, articulated and mobile it is. When we think about a joint like the ankle we might think about something like a horseshoe with a bolt across the open bit and something like a block with a hole drilled through it hanging off the bolt. Ok, maybe that's just me.

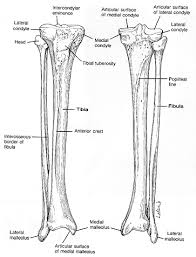

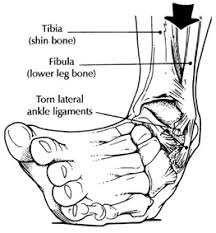

The ankle joint is intriguingly more intrigued. The first bit of the ankle is that the bumpy bits that we feel and bang have names: malleoli. The malleoli are the bumpy bits at the base of the two bones that make up the shin: the bigger tibia that the femur rests upon for knee action with all that meniscus cartilege and acl/mcl joints, and the fibula, the smaller, thinner balance bone. The structure is similar to the lower arm's radius/ulnar double boning.

So ok, we have the malleoli that act as kind of connectors from the leg to the foot.

Talus/Calcaneus.

Talus/Calcaneus. Now it seems to me things get really impressively remarkable. The malleoli move atop a bone that sits atop a bone.

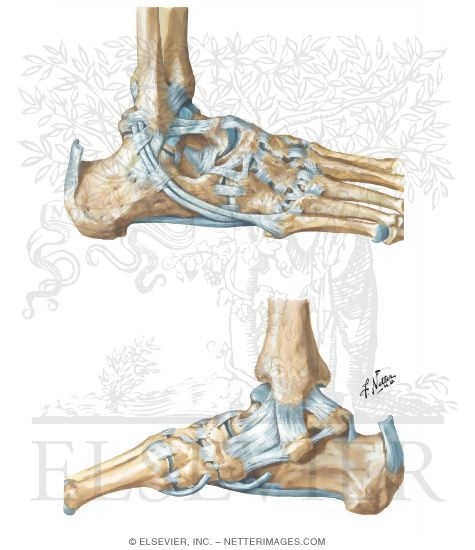

Let's go slowly (at least for me): the part of the foot that hits the ground at the back is the calcaneus. The bone that sits on top of this - doesn't touch the ground at all - is the talus. The malleoli articulate around the talus. The ankle joint therefore or what we think of as the ankle is actually four bones and three joints: bones are the tib and fib and the talus/calcaneus. The joints are the lateral malleoli with the talus, the medial malleoli with the talus and the taleo-calcaneal joint.

From all these connections, we might get a bit more clearly why the ankle may be vulnerable to sprain.

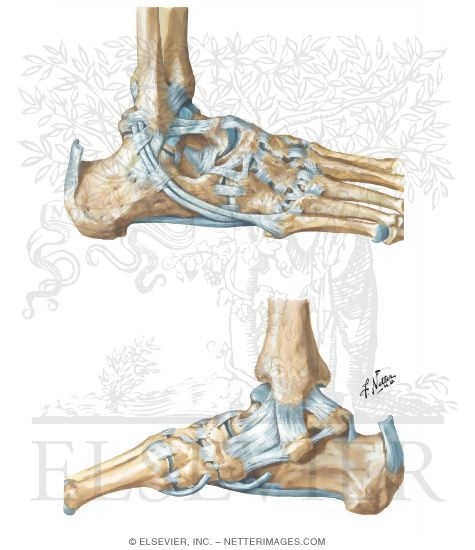

Just take a look at how intriguing the lacing is of the bones of this joint.

It Moves! It's ALIVE

|

the lacing of the malleoli with the taleo/calcaneal

joint. |

An important thing to note, i think, to help conceptualize the ankle that goes beyond the first part of this post is that we're talking a complex mechanics here, not just a hinge joint.

When we say the achiles tendon conncects to the bone at the base back of the foot, pulls it, and the ankle bends, that sounds pretty simple. And it's a true statement, for a given granularity of truth. But those three joints in just the ankle - never mind the rest of the foot - suggest that the motion may be a little more suble. The achiles does pull on the calcaneus, but it's wrapped atop the talus, which is slotted between the malleoli - which as we see in the illustrations above is way forward of the tendon and also way above that pull point.

We're not even touching on the talus/calcaneus being the back stop for the little tarsals of the foot before getting to the bones that end up through multiple joints into the toes.

What's my point: with this many joints, that's a whole lot of movement going on.

Why have this much movement that we need three joints in the ankle alone?

The foot is how we usually first encounter the world. It lets us stand with the feet in full contact with the earth while we get our butt back and move our knees in, in our athletic ready stance. The foot can do this because its multiple joints support multiple angles of movement while still wrapping around some uneven surfaces and especially while distributing load from the rest of the body across some spingy shock absorbers. I could just go on and on about the miracle of the foot with 24 percent of the bones of our body in those two feet.

|

multijoint action allows for sophisticated

movement around the joint

while staying vertical - when

we don't practice these movements

we can hurt the lacing that has no

practice with the strain at end

range of motion |

Since we're focusing on the ankle for the pistol, though, an important part to bear in mind is that the talus doesn't simply pivot like there's a bolt through one end of the malleoli to the other. There is give, movement as we move the joints in their capsules. For instane, As we bend the knee forward towards the foot on the floor, someone putting their fingers on our malleoli should feel the malleoli roll back - a wee bit - but back nonetheless. The two shin bones move back on the talus. IT's movement we can feel, especially as we practice ankle movements for mobility. Likewise, the lateral (side to side) movements of the ankle happen becuase of the shape of the bones, and also because of the flexibility of the tendons. Tendons are not always pulled up super tight. Muscles pull on them; different positions relax them and so on.

Take away: ankle movement is a complex interoperation of joints. To dorsiflex well in our ottoman pistol, we need to be sure our foot feels comfortable supporting dorsiflexion without collapsing (everting - the opposite direction to the movement shown in the image above).

One of the best ways to help the ankle is actually to work with all the joints: if there's an oddity in hip movement or knee movement or shoulder movement, that might show up in the ankle. The site of an issue isn't always the source.

That said, unless we have a movement practice, most of us don't do movement practice with our feet. Leaning in and out on the ankles from a tall spine - without having to involve the hips - is a potent practice. So is placing our foot behind us and resting on the top of the foot from multiple angles. Each of these motions helps lubricate the joints and tendons, but also practices the movements we need to control in our squat. Shoes that pass the twist test with mobile soles, and that let our ankles move more while walking are also great aids to better foot and gait practice.

SUMMARY

Muscularly, at the ankle in the pistol, the big players are the calf muslces, the soleus and gastrocs, as they eccentrically contract to help let the knee bend forward by braking that forward action by paying out the musculo/ligamentary line at the back of the leg/foot to let the shin come forward towards the ankle.

Joint Wise. The ankle is an interesting set of joints that are ligament to bone to musculo-tendonal levers. It acts like a hinge and like a ball in socket and like an inertial damper for load.

Improving that Base of Support. Sometimes just some simple movement work can improve the action of the joint *just* because they give the joint some practice in moving and practicing its range of motion - with and without load. Please note, we're not talking making the ankles either more stable or more mobile; we're talking simply about supporting whatever their movement needs are for the particular motion.

Recommendations. Please note: no one said that to improve dorsiflexion or ankle control, we need to stretch before squatting. No. We did not. A bit of a discussion around why not, here (

threat and movement) and here (

what's a warm up)

You're perhaps familiar with the approach i've found successful for myself and the folks i coach:

i like z-health movement work for loaded and unloaded movement practice. THe movement template ensures that we get practice in a variety of positions/tensions/challenges. Doing this kind of joint prep work has been shown in some research to help reduce incidence of injury (see

By Test Stronger section of this post). That's good. And decent control means better pistol.

Sometimes getting to that control may also mean some prelim practice work before going for the ottoman, both to reduce

neuro-perceived threat and sometimes just plain old stress (

tips for that one). If you'd like some help with dialing in what you need to succeed here,

consider a coach - one who can do a

movement assessment maybe even too. Master ZHealth Practitioners

Ken Froese and

Lou McGovern (

remember his excellent tip for improving the press?) have pioneered using a movement with the sphenoid to help get people who haven't pistoled to pistol. We're just that complex and amazing.

|

| yup, the sphenoid |

Heres to enjoying our movement.

Pistol Resources:

-

beast skills site

- Pavel Tsatsouline's

The Naked Warrior

- Steve Cotter's

Mastering the Pistol

Thanks for viewing this series. Hope it helps you enjoy your ottoman pistol practice even more

Related Ottoman Pistol Posts

THis how to get on track and stay on track is the subject of a jointly authored book and web site and

THis how to get on track and stay on track is the subject of a jointly authored book and web site and